By Michelle E. O’Brien and Tom Irving

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit today affirmed the U.S. Patent Office’s findings that claims in four patents were unpatentable because they are not patentably distinct from claims in other patents in the same family. In re Cellect, LLC, Nos. 2022-1293, 2022-1294, 2022-1295, 2022-1296 (August 28, 2023). In view of the oral argument, the outcome of this case was virtually certain. It has nonetheless been watched carefully because of the implications it will undoubtedly raise.

The issue before the court was, at its core, a straightforward one—was the decision by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) finding the challenged claims unpatentable for obviousness-type double patenting (ODP) to be affirmed? In the appeal, the court noted that for the first time, it was addressing how a statutorily authorized extension, Patent Term Adjustment (PTA), interacts with ODP.

Obviousness-Type Double Patenting

ODP is a “judicially created” doctrine that “prohibits an inventor from obtaining a second patent for claims that are not patentably distinct from the claims of the first patent.” See In re Lonardo, 119 F.3d 960, 965 (Fed. Cir. 1997). “There are two justifications for obviousness-type double patenting: to prevent unjustified timewise extension of the right to exclude granted by a patent no matter how the extension is brought about and to prevent multiple infringement suits by different assignees asserting essentially the same patented invention.” In re Hubbell, 709 F.3d 1140, 1145 (Fed. Cir. 2013).

In most ODP situations, the analysis of whether a claim of a subject patent is invalid or unpatentable as an obvious variant of a claim in a reference patent involves a one-way analysis, i.e., whether the challenged claim is an obvious variant of the reference claim, but not vice-versa: “[a] later patent claim is not patentably distinct from an earlier patent claim if the later claim is obvious over, or anticipated by, the earlier claim.” Eli Lilly & Co. v. Barr Labs. Inc., 251 F.3d 955, 968 (Fed. Cir. 2001). Therefore, in post-URAA patents (all the patents at issue were post-URAA), the determination of whether a patent is properly considered as a reference patent depends on whether the expiration date of the reference patent(s) is earlier than (proper as a reference patent) or later than (not proper as a reference patent) that of the challenged patent(s). Novartis Pharms. Corp. v. Breckenridge Pharm. Inc., 909 F.3d 1355, 1362-63, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2018). We know from Gilead Sciences, Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd., 753 F.3d 1208 (Fed. Cir. 2014), that even if the reference patent issues after but expires before another patent, the earlier-expiring patent can qualify as a double patenting reference for that other later-expiring patent.

Thus, the question of whether the ODP analysis is performed before or after any PTA is added may be outcome determinative, in that it may decide whether an asserted patent even qualifies as a reference patent—if a patent does not qualify as a reference patent, the subject patent may avoid the ODP challenge all together.

Procedural Background of Cellect

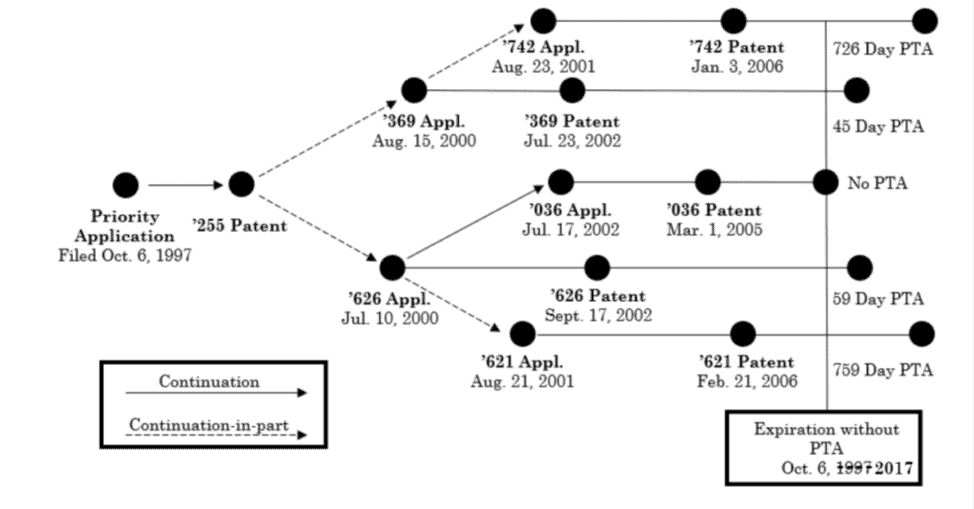

In four reexamination proceedings in the U.S. Patent Office, certain claims of Cellect’s U.S. Patent Nos. 6,982,742, 6,424,369, 6,452,626, and 7,002,621 were challenged by Samsung as unpatentable due to ODP based on patents in the family that trace back to U.S. Patent No. 6,862,036 (‘036). Each of the challenged and reference patents was part of the same family, with all claiming priority back to an application filed on October 6, 1997; thus, the patents were all post-URAA patents subject to a term of 20 years from that date. None of the patents at issue in Cellect was subject to a terminal disclaimer during prosecution. As such, and as seen in the chart below, each of the challenged patents and the reference ‘036 patent would originally expire on the same date, October 6, 2017 (the date in the chart is wrong), under 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(2), except that some had received patent term adjustments pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 154(b):

Cellect sued Samsung, but Samsung successfully requested ex parte reexamination. In each of the reexams, the Examiner finally rejected the challenged claims, finding they were “not patentably distinct” from claims of various other patents in the same family. The unpatentability of all claims under ODP traced back to the ‘036 patent, which did not receive PTA.

Cellect appealed those rejections, at a time when the challenged patents were all expired, to the PTAB. In its appeal, Cellect did not argue that the challenged claims were patentably distinct; rather, they argued that the ODP analysis should be undertaken based on the original expiration dates of the patents, not the expiration dates after PTA was applied. In other words, that expiration date, absent PTA, for all patents would have been October 6, 2017.

In affirming the Examiner, the PTAB considered ODP in the context of the two ways Congress has authorized prolongation of a patent’s term: PTA available under 35 U.S.C. § 154(b) (adjustment of patent term due to USPTO delays) and PTE available under 35 U.S.C. § 156 (extension of patent term due to US regulatory delays). Noting that the “Federal Circuit has already addressed similar questions for a PTE,” the question before it in the appeals was “how a PTA under § 154 should factor into the double patenting analysis, such as whether double patenting should be based on the expiration date before a PTA or after.”

Discussing Merck & Co. v. Hi-Tech Pharmacal Co., 482 F.3d 1317 (Fed. Cir. 2007), the PTAB summarized the issue there as whether a PTE under § 156 could be applied to a patent subject to a terminal disclaimer. In Merck, an ODP rejection was made during prosecution and Merck filed a Terminal Disclaimer disclaiming a portion of the term of the patent at issue. The patent was later awarded 1233 days of PTE. In rejecting Hi-Tech’s arguments that the extended term was invalid due to the Terminal Disclaimer, the court held that “a patent term extension under § 156 is not foreclosed by a terminal disclaimer,” and that the “Hatch-Waxman patent term extension is from the expiration date resulting from the terminal disclaimer and not from the date the patent would have expired in the absence of the terminal disclaimer,” citing Merck at 1322-23. The PTAB explained that the court in Merck reached this conclusion by contrasting PTE with PTA, and noted that although § 154 expressly addresses instances in which a Terminal Disclaimer had been filed, § 156 contains no such provision. The PTAB concluded, therefore, that “a terminal disclaimer is applied before a PTE because PTE is different than PTA.”

The PTAB also considered the case Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures LLC, 909 F.3d 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2018). In Novartis, similar to the Cellect appeals, the patent containing claims challenged as patentably indistinct from those of a reference patent expired after the reference patent solely because of statutorily-mandated PTE awarded to the challenged patent, and no Terminal Disclaimer had been filed. The question in Novartis, therefore, was whether the PTE-awarded patent was invalid based on ODP over a reference patent which would not expire earlier than the challenged patent but-for the PTE in the challenged patent. The PTAB highlighted the fact that in answering this question “the Federal Circuit not surprisingly held ‘as a logical extension of our holding in Merck & Co. v. Hi-Tech‘ that double patenting also should be considered before a PTE,” citing Novartis, 909 F.3d at 1373-74.

Turning to the case before it, the PTAB was not persuaded that Novartis should be extended to PTA “because it ignores the plain text of § 154 and the actual holding in Novartis v. Ezra.” The PTAB reasoned “the question is whether double patenting should be considered with the expiration dates before or after a PTA.”

The PTAB also highlighted the fact that Merck drew a distinction between the statutory language found in § 154, referencing patents in which a Terminal Disclaimer had been filed, and the absence of any such reference in § 156, and concluded that “the rule in Merck v. Hi-Tech and Novartis v. Ezra for when to apply a PTE does not apply to a PTA because those decisions were premised on the contrast between PTE and PTA.” The PTAB concluded that “the statutory language of § 154 is clear that any terminal disclaimer should be applied after any PTA….” Because § 154(b)(2)(B) expressly prohibits adjusting a patent’s term beyond the date specified in a Terminal Disclaimer, the PTAB determined that Congress implicitly also addressed ODP in this section of the statute because ODP and Terminal Disclaimers are “two sides of the same coin.” Therefore, the PTAB held that the ODP analysis should be conducted after PTA is added.

As a result, the PTAB affirmed the Examiner’s ODP rejection of all challenged claims, and Cellect appealed.

Federal Circuit Decision

In its appeal, Cellect maintained its argument that PTA should not be treated differently from PTE, and that the ODP analysis should be performed based on the expiration dates of the reference and subject patents before PTA is added. In support, Cellect argued that Congress intended that both the PTE and PTA statutes grant term extensions or adjustments to compensate for regulatory (FDA) or PTO delay, and both mandate that such extension or adjustment is awarded when the statutory conditions are met (“shall be extended…”). The court disagreed, finding that Cellect’s argument “is an unjustified attempt to force disparate statutes into one.”

Recognizing that the issue, i.e., how PTA interacts with ODP, before it was one of first impression, the court emphasized that “[t]he PTE and PTA statutes have quite distinct purposes.” It noted that § 156 limits the extension to “a single invention,” but that treating § 154 similarly would “effectively extend the overall patent term awarded to a single invention…by allowing patents subject to PTA to have a longer term than the reference patent.”

Like the PTAB, the court looked to Merck and Novartis and the language of the statutes themselves for guidance. The court focused on the absence of any mention in § 156 of whether PTE is available for a terminally-disclaimed patent in contrast to the express statement in § 154(b)(2)(B) that PTA is not available for a patent in which a Terminal Disclaimer has previously been filed.

Agreeing with the PTAB that ODP and Terminal Disclaimers are “two sides to the same coin,” the court stated that “the statutory recognition of the binding power of terminal disclaimers in

§ 154(b)(2)(B) is tantamount to a statutory acknowledgement that ODP concerns can arise when PTA results in a later-expiring claim that is patentably indistinct.” As Cellect did not take the position that the claims were patentably distinct, the court observed that Cellect had the opportunity to file a Terminal Disclaimer but didn’t. Correctly recognizing that had it done so, that section of the statute would have precluded the patents from receiving PTA, the court explained that by not having filed Terminal Disclaimers the “clear intent of Congress” set forth in

§ 154(b)(2)(B) was “frustrate[d].”

The court concluded, therefore, that “our case law and the statutory language dictate an outcome where an ODP analysis must be performed on patents that have received PTA based on the expiration date including PTA.” In other words, the expiration date to consider for any reference or subject patent in the ODP analysis is the expiration date with any PTA included.

As noted above, the court’s affirmance of the PTAB was not unexpected. At the hearing, the panel focused on the fact that Cellect was not arguing that the claims were patentably distinct, and the judges were clearly concerned about the fact that the patentee had already received its full 20-year term for inventions that were not patentably distinct. We could argue about the merits of the decision, but the fact remains that unless Cellect requests rehearing or petitions for certiorari, this precedential decision means that patent applicants and patentees should consider strategies to minimize the impact on their current patents and patent portfolios, as well as pending applications.